Are LLMs Just Next Token Predictors?

It is a common refrain that large language models are trained to “predict the next token.” I take this to mean that LLMs are built to be short-sighted: they’re focused only on the next token, and insofar as they consider the possible directions of future text, it is just to be better at predicting the very next token. Moreover, all of their internal mechanisms are constructed in pursuit of this goal.

This idea is often challenged when it is applied to RL post-trained models. Reinforcement learning training gives them more of a clear signal from the long-term course of text. A whole chain of text can be evaluated at once, depending on how well it turns out. But I’ve never heard the next-token-prediction framing challenged for base pre-trained models. A superficial look at the training process may make this seem obvious that base LLMs can only be next token predictors, but the full story seems to me to be more complicated.

The Gradient Flow Story

LLM models are unquestionably trained, at least in part, to be better at producing outputs that are similar to input text. This is a form of prediction. During the first stage of training, their parameters are set through a random initialization of values and run through a long process of continual adjustment so that their outputs serve as good predictions.

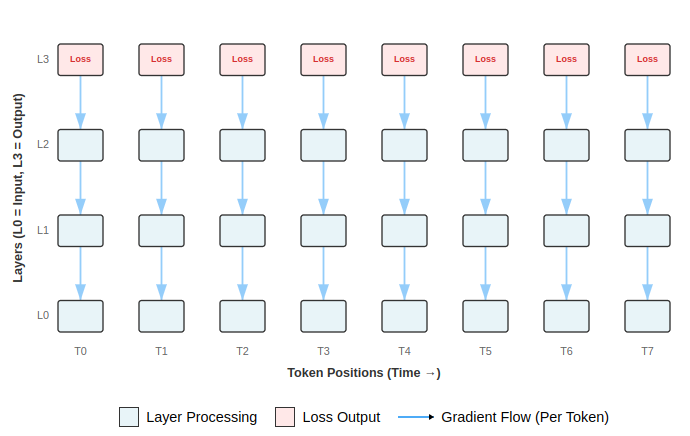

The pretraining phase contains training on existing (ideally human-written) text documents. When trained on a document, the document text is converted into numerical tokens, and the model is run on every token in that document at once. It produces as outputs probability distributions for each token at each point.

The loss of a model’s output token probability distributions is computed by comparing the output of the model after each token against the actual next token in the document. We can see how parameters contribute to the final prediction, and how they would have contributed had they been a bit different. That signal loss is then used to change parameter values in whatever direction would have helped make the outputs a better prediction.

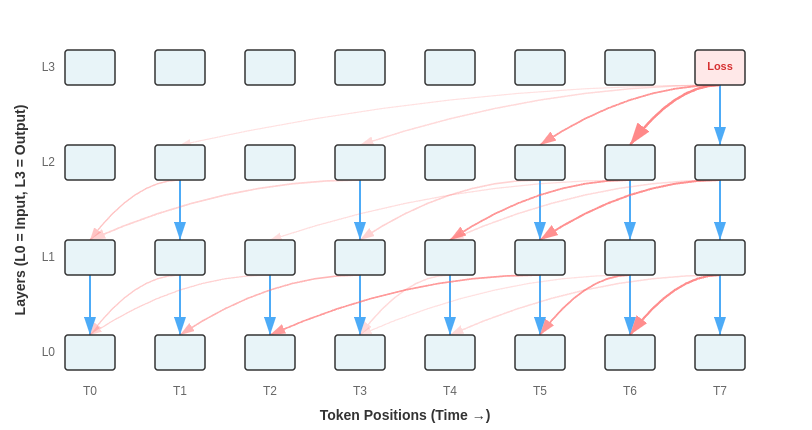

LLMs are hierarchical. Loss is projected backward through the parameters, such that every parameter that contributed to the output stands open to be modified. When you backpropagate through a transformer, the gradient from that final token prediction flows both down layers and backward through attention mechanisms to the computations performed on previous tokens. Attention creates a dense graph of connections: every token attends to many previous tokens, so gradients flow from each position back to everything it paid attention to, and potentially everything they pay attention to, and so on.

The same parameters are applied to each token. The direction of update for a parameter therefore depends on how it figures into to every prediction simultaneously. A parameter may therefore have many different routes to impacting the overall result, and how it is changed may be influenced by each contribution separately.

This means the “signal” from failing to fully predict token N gets spread out across the ways that tokens 1 through N-1 are handled. For each prediction N, each of the prior key and value parameters gets updated to be more helpful to making the prediction at N. And for each key and value matrix in each attention block, all of the parameters touching the residual streams that feed into those matrices get adjusted to better produce the right activations.

But why should we think the retrospective signal dominates?

When gradients flow backward through attention, the processing of each token gets updated based on how useful it was as context for all the queries that attended to it and for predicting the very next token. For most tokens, this means the next few dozen tokens in the sequence all contribute - that’s a plausible window where attention weights are substantial.

So a token at position 10 receives loss signals from:

Predicting token 11 (the “next token” signal)

Being attended to by tokens 11, 12, 13... up to maybe token 30 and contributing to their predictions

Contributing to representations in tokens 11…30 that are attended to by tokens 12…50.

Etc.

That’s a number of gradient signals about “how should you represent yourself to be useful context” for every one signal about “what should you predict next.” The attention is weighted, so these signals may not be as strong, but their numerosity could make up for their weakness.

Some tokens surely get even more retrospective signal - important nouns, the subjects of sentences, key entities, perhaps final punctuation - these might be heavily attended to by tokens 50 or 100 positions later. These tokens would make more sense to optimize as long-term context.

Even for semantically simple tokens that only matter locally, they’re still getting an order of magnitude more “be good context” signal than “predict immediate next token” signal.

The exact ratio varies, but the structural fact remains: attention ensures that much of the gradient signal is about context provision, not just prediction.

What Are We Really Training?

If you wanted to literally train a “next token predictor,” we might opt for a simpler architecture: process the context, output a prediction, and backpropagate loss just over the mechanisms that consume that context, not the mechanisms that generate that context. The backward pass would update parameters based on “you saw context X and should have predicted Y.” This likely wouldn’t actually do too well at predicting text. It could never accumulate the context it would need to make a smart prediction at the final token.

Transformers update both mechanisms at once. The attention mechanism ensures that during training, every token is being optimized not only for what it should predict, but also for how it should participate in the prediction of everything downstream from it.

We might instead think of models as built to be future token predictors rather than next token predictors. But this is a vague gloss that misses out on something important. Each token learns to represent itself in whatever way makes it most useful for the predictions that will follow. Models are primarily optimized to provide good context for future predictions.

The model must also make immediate next-token predictions using these same representations. It has to do short-term prediction with machinery that’s been optimized simultaneously for long-term context provision.

This creates an interesting dynamic:

Context Pressure: Represent the conversational context up to now so that 5-20 tokens from now, the model can make good predictions

Prediction Pressure: Predict the very next token as well as you can with whatever representation you’ve built

This reframing suggests why models can be:

Excellent at tasks requiring medium-range coherence

Quite cognitively flexible: able to follow conversations that veer in different directions

Capable of generalizing beyond pure prediction

The next token is the measure, but context quality over the next few dozen tokens may be what training on the prediction loss predominantly optimizes for.